Not long ago I received a message from a tugboat crew member who had witnessed the events of 9/11 from the waters around Lower Manhattan. He had taken video from his boat of the burning twin towers of the World Trade Center that recorded the last moments of victims who fell or leapt to their deaths. As he filmed, he spontaneously narrated the horrors, using salty language and a tone that, in retrospect, didn’t fit the enormity of the events. His sense that his comments were disrespectful haunted him and he never shared his footage publicly, even though he knew that the recording would be a valuable addition to the historical record.

The passage of time, like flowing water, creates a channel through even the hardest stone. When he contacted me, the mariner said the years had revised his thinking: “Now I know it’s more important for everyone to see and know what happened that day, versus some comments I made,” he wrote in an email. I viewed a copy of his video then connected him with archivists at the National September 11 Memorial & Museum in New York who gratefully included it in their unparalleled collection.

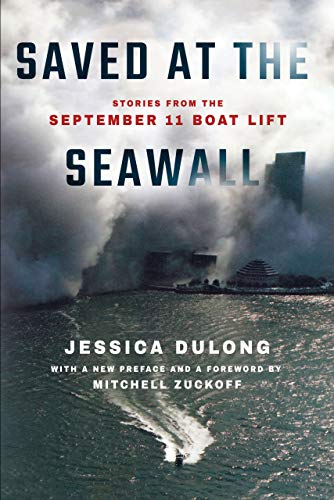

That story came to mind as I read Jessica DuLong’s remarkable book Saved at the Seawall, which filled a large gap in my own knowledge and research. Her work has brought to the surface long-overlooked tales of heroism and sacrifice, recounting the actions and sharing the character of a community response to tragedy as immediate and impressive as any in history.

Major facts about September 11, 2001, are well established: 19 terrorists acting on behalf of Al Qaeda and Osama bin Laden hijacked four commercial passenger jets and turned them into guided missiles aimed at government and civilian targets,

killing nearly 3,000 people in New York City, Shanksville, and Washington D.C. Those murders reshaped the world, and we are still coming to understand this new political, economic, social, and diplomatic terrain. It is for good reason, then, that 9/11 is among the most exhaustively examined moments of the past century. And yet, 20 years later, essential, insightful, and unique perspectives are still coming to light—and deservedly so.

All of us who write about 9/11 are indebted to the New York Times for, among other reasons, the newspaper’s “Portraits of Grief” project. In brief vignettes, gifted reporters and writers memorialized and humanized the victims. Their work began almost immediately after the fall of the towers, the fires at the Pentagon were extinguished, and recovery began in the field where United Airlines Flight 93 crash-landed, and it continued for years. The Times reporters told the stories of the dead in 2001 and then followed up with accounts that revealed how those left behind were coping, or not. By taking such an intimate approach to attacks of enormous scale and complexity, the newspaper declared that every individual loss deserved thoughtful, sustained attention and that every perspective and experience of 9/11 merited deep reflection.

Which brings me back to DuLong, who has extended the project begun by “Portraits in Grief” by listening to and then presenting the words of individuals who suffered and persevered on that bright September day and then long afterward. In this gripping narrative, if readers will forgive the expression, DuLong has gone into uncharted waters of recorded history.

Overwhelmingly, the study of 9/11 has focused on what happened in the air and on the ground. Entire books have been written about Flight 93, whose 40 passengers and crew members fought back against the hijackers and brought down the plane well short of its intended target in Washington, D.C. Other books have examined the military response, or the Pentagon fire, or the fall of the twin towers. Many have told the tale of a single survivor, hero, or victim. The same ground-and-air focus characterizes my work, first covering the attacks as a reporter for the Boston Globe and then writing a book-length narrative about 9/11.

By taking to the water, a fitting decision considering her own rich history on the Hudson River, DuLong has applied her hard-earned maritime knowledge in the name of honoring the men and women who answered the ancient code that compels mariners to proceed with all speed to a distress call. Like firefighters, the captains and crews who took part in the 9/11 boat lift moved toward danger, putting themselves in peril, to save others. Their obligation wasn’t legal but moral.

DuLong knows why these roughly 800 mariners aboard at least 150 watercraft in New York Harbor answered the call, and now we can, too.

Mitchell Zuckoff, author of

Fall and Rise: The Story of 9/11