As the sun tracks across the sky on this overcast, 78-degree morning, the clouds part ways leaving behind a mazarine blue. There is no dust. No smoke. The heaviness in today’s air is only the humidity of late summer. A forest of sailboat masts bobs in the rectangular notch of Manhattan’s North Cove. The propeller wash from New York Waterway and Liberty Landing ferries dropping off and picking up passengers at the new World Financial Center terminal, 150 paces or so to the north of the small harbor, pushes little waves through the 75-foot gap in the breakwater. Mis Moondance, a 66-foot charter yacht, motors in and maneuvers into a slip among the wooden floating docks. A blue and white police boat holds station just outside the cove’s entrance, blue light flashing above the pilothouse.

To a casual observer, unaware of the date, it might be hard to say if this quiet is just the regular hush of Sunday or something more solemn. Certainly the pedestrian plaza is far less populated on Sundays than it would be on a weekday morning—a Tuesday morning, say. Surely all the street closures and police barricades thwarting access have kept some people away, while reminding any who might have momentarily forgotten that this is no ordinary day.

Several blocks inland, beneath the trees in the National September 11 Memorial plaza, the fifteenth anniversary commemoration has begun. About 8,000 people have assembled for this year’s annual ritual. Families of those lost will read, 30 at a time, the names of the 2,977 people who died from injuries or exposures sustained 15 years ago today, plus the six killed in the bombing of the World Trade Center on February 26, 1993.

At 8:46 a.m., bells ring in the plaza and across New York City to announce the first of six moments of silence. This one marks the moment when American Airlines Flight 11 ripped through the northern facade of the World Trade Center’s North Tower between the ninety-third and ninety-ninth floors. By the water’s edge, the chuff-chuff-chuff of a helicopter hovering over the Hudson never lets up. Silence on the waterfront is merely theoretical.

Sunday joggers, earbuds in, digital music players strapped around biceps, continue on their morning runs. Bicyclists keep biking, tourists snap photographs, parents herd young children. But two New York Waterway ferries pause, foregoing their usual over and back, over and back, to linger in reverence. Above them glints the new 1 World Trade Center, the base of its spire reflected in an adjacent skyscraper, also new. Between them stands a third tower, still under construction, the outstretched arm of a crane loitering above its uppermost reaches—a skeleton waiting for workers to finish grafting on its reflective skin.

When the bell chimes again at 9:03 a.m., the moment that United Airlines Flight 175 crashed into the South Tower’s southern facade between the seventy-seventh and eighty-fifth floors, a lone gentleman with close-cropped gray hair is sitting silently before the cross inside St. Joseph’s Chapel where a special anniversary mass is scheduled to commence at 10 a.m., one minute after the South Tower fell, and 28 minutes before the North Tower followed it to the ground.

The day after the attacks, this chapel was converted into a makeshift, volunteer-run supply house for distributing donated goods. Rescue workers turned its plate glass windows into a message board of sorts, tracing pleas, prayers, and pronouncements into the gray dust: “Revenge is sweet.” “Goodness will prevail.” “It doesn’t matter how you died, it only matters where you go.” “You woke a sleeping giant.” Among the scrawls was the word “Invictus.” Latin for unconquerable, it’s the title of an 1875 poem by William Ernest Henley that begins:

“Out of the night that covers me,

Black as the Pit from pole to pole,

I thank whatever gods may be

For my unconquerable soul.”

Other messages, more practical than poetic, included: “Go to Stuyvesant High School to sleep” and “Lt. John Crisci call home.” I first transcribed these missives into a small reporter’s notebook while standing in the dust of September 12, 2001. Although I wasn’t technically reporting at the time, a writer’s lifelong habits run deep. I scribbled down the words in an attempt to collect the details that I hoped might somehow help me make sense of the unfathomable ruination at hand. At 28 years old, I was still a newcomer to New York City, having moved here in January of 2000. By the following September, I was just six months into the hands-on apprenticeship that had launched my new career as a marine engineer. I was a novice in every sense of the word.

Now, a decade and a half later, I’ve risen from assistant engineer to chief, a “hawsepiper” who’s come up through the ranks (climbing, metaphorically, up the anchor chain through an opening in the bow called the hawsepipe) by learning on the job rather than in school. New York harbor’s maritime community is my community.

After 15 years in the industry, my view of everything has changed. Now, on this overcast Tuesday morning, when I notice the dull red paint coating one section of the curved steel railing along the water’s edge, I recognize it as primer, evidence of a painting project in process. This is the railing that I climbed over, on September 12, as I bolted from threats of a fourth building collapse, scrambling to board the boat that had so recently become my workplace: retired 1931 New York City fireboat John J. Harvey. No longer an active-duty vessel with the Fire Department of the City of New York (FDNY), the boat had been operating as a preservation project and living museum when it was called back into service to help fight New York City’s most devastating fires.

A fireboat is essentially a huge pump, several pumps, in fact, which is exactly what was needed that day. And so fireboat Harvey’s all-volunteer, all-civilian crew (save for our captain, a retired FDNY pilot) worked alongside active-duty fireboats to pump Hudson River water to land-based battalions. Fire mains lay broken. Hydrants were buried beneath debris. For days following the twin towers’ collapse, fireboats provided the only firefighting water available on site. When firefighters bent over their hoses to rinse the dust from their faces, they sputtered and spit in surprise at the taste of salt from the Hudson.

Supporting pumping operations aboard fireboat John J. Harvey was the work that had brought me to Ground Zero. I’d spent the eleventh like so many others: glued to the television, then wandering around my Brooklyn neighborhood trying unsuccessfully to donate blood. My identity as a mariner was not yet ingrained. As I’d watched the staticky news coverage on the only channel that would come in on my television set, it hadn’t occurred to me that the antique, decommissioned fireboat where I was spending more and more of my days as a budding engineer could offer the opportunity to help that I so desperately sought. And so I missed the boat lift.

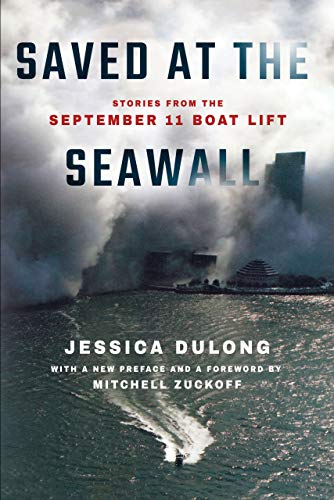

As thick, gray smoke began spilling through the airplane-shaped hole in the World Trade Center’s North Tower, civilians caught in an act of war—some burned and bleeding, some covered with soot—fled to the water’s edge, running until they ran out of land. Never was it clearer that Manhattan is an island. Within minutes, mariners had raced to meet them, white wakes zigzagging across the harbor. Long before the Coast Guard’s call for “all available boats” crackled out over marine radios, scores of ferries, tugs, dinner boats, sailing yachts, and other vessels had begun converging along Manhattan’s shores. Hundreds of mariners shared their skills and equipment to conduct a massive, unplanned rescue. Within hours, nearly half a million people— adults and children—had been delivered from Manhattan by boat.

This became the largest waterborne evacuation in history— more massive even than the famous World War II rescue of troops pinned by Hitler’s armies against the coast in Dunkirk, France. In 1940, hundreds of naval vessels and civilian boats rallied to rescue 338,000 British and Allied soldiers over the course of nine days. But on September 11, 2001, boat crews evacuated an estimated 400,000 to 500,000 civilians in less than nine hours. The speed, spontaneity, and success of this effort were unprecedented.

In the years since, countless shattered lives have been remade, fractured families reconstructed, loves lost and found. “The Pile”—16 acres of wreckage left at the World Trade Center site— was eventually excavated and redubbed “the Pit” before being transformed into a memorial with twin reflecting pools that occupy the square footprints of the vanished towers. Americans’ pre-9/11 sense of security, along with a misbelief in our immunity to the carnage and cruelty suffered by the rest of the world, was sabotaged and replaced with a gnawing “new normal.” This post-9/11 “afterward” was characterized by anxiety and suspicion coupled with an acquiescence to new infringements on privacy and freedom. But what also arose in the aftermath of the deadliest terrorist attacks on U.S. soil was a heightened sense of goodwill, an abundance of comity, and an instinctive impulse to help. Amid the darkness and chaos, a series of lifesaving, selfless acts transformed the waterfront of New York harbor into a place of hope and wonder.

By the time I arrived at the trade center, tugs and other vessels lining the seawall had shifted gears from ferrying people to running supplies and other critical support operations. In the hazy, horror-filled, dust-choked days that followed, I didn’t grasp how history had been made along Manhattan’s shores. Indeed, still today few people recognize the significance of the evacuation effort that unfolded on that landmark day. This book addresses that omission. The stories that follow are the culmination of nearly a decade of reporting to discover how and why this remarkable rescue came to pass—what made the boat lift necessary, what made it possible, and why it was successful.

On any given Tuesday in 2001, you could stand at the southern tip of Manhattan Island, gaze out over the water, and watch the busyness of New York harbor unfold before your eyes. You’d doubtless notice a Staten Island Ferryboat, in all its enormous orange glory, bridging the 5.2-mile gap between the two island boroughs. Looking up the west side, you’d see smaller white and yellow fast ferries darting across the three-quarter-mile span of the Hudson that separates Manhattan from New Jersey. Maybe you’d track the movements of a recreational sailor, playing hooky on a weekday, tacking back and forth through the sparkling salt water to drink in the last of the summer sun. Over toward the east side, on the approach to the half-mile expanse of the East River between Manhattan and Brooklyn, you might lay eyes on a black-hulled freighter making its way to tie up at the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

Scanning across the waters straight ahead, your view bracketed by container cranes in Brooklyn’s Red Hook Terminal on the left and Port Elizabeth’s and Port Newark’s on the right, you’d perhaps catch glimpses of the working harbor carrying out its workaday business: a tugboat pushing barges filled with scrap metal or stone; another tug in the anchorage securing empties to await a fair tide; a North River-bound bulk freighter, the booms of its white deck cranes outstretched like dueling swords; a containership, nudged along through the channel by ship-assist tugs. Or maybe you’d even spot a “honey boat” hauling sewage sludge from local wastewater treatment plants, or an Army Corps of Engineers drift collection vessel plucking flotsam from the water to remove hazards to navigation. Together these watercraft, working side by side, under the oversight of the U.S. Coast Guard, perform the critical functions of the Port of New York and New Jersey.

Still, much of the activity of New York harbor would remain unnoticed. A quick tour of the numbers reveals how much activity there was in September of 2001. Back then, New York harbor provided passage to 91,600 commuters and accommodated between 25 and 30 large, international, deep-draft, commercial vessels on an average weekday. Including 30 billion gallons of petroleum and petroleum products, more than $93 billion worth of cargo moved through the port annually, generating a total of $29 billion in economic activity while serving more than 17 million customers in the states of New York and New Jersey. More than 167,000 people made their living directly from all this traffic.

New York harbor was, and is, a busy place—the third largest container port in the United States and a vital connection between New York City and the rest of the world. But other than the passenger ferries, whose crews interface directly with their customers, much of the hard work of the harbor’s working watercraft happens—now, as it has since the latter half of the twentieth century—largely out of view. Manhattan is an island, and the realities of island real estate are what ushered the port’s industries off Manhattan’s shores and over to Brooklyn, Staten Island, and New Jersey in the 1960s and ’70s.

Although port workers handle nearly every item in New Yorkers’ home and work lives on its arrival from overseas, most residents hardly give the harbor a passing thought. By late 2001, the last vestiges of the borough’s working waterfront had been rapidly uprooted and replaced with sparkling esplanades festooned with iron railings and polished stone. Maritime infrastructure (cleats, bollards, fendering, and other features necessary for a safe tie-up) had been replaced with ornamental fencing. An island that had once berthed legions of vessels now had a waterfront that was mostly geared toward recreation and people’s enjoyment of a passive view.

On September 11, 2001, as the cascade of catastrophe unfolded, people found their fates altered by the absence of that infrastructure and discovered themselves dependent upon the creative problem solving of New York harbor’s maritime community— waterfront workers who’d been thrust beyond their usual occupations and into the role of first responders.

“It was a jet. It was a jet. It was a jet.” The time was 8:46 a.m.

Patrick Harris had been sipping coffee at the open helm of his 63-foot wood sailing charter yacht Ventura, chatting with the boat’s maintenance man, when he heard the roar of engines up close. He looked up in time to watch the tail of a jet airplane penetrate the north face of 1 World Trade Center, less than 1,000 feet away from where his boat was tied to a floating dock in North Cove, the small harbor notched out of Manhattan’s western shore where the World Financial Center meets the Hudson.

“In my mind’s eye I can still see a frozen Kodachrome of the tail end of the aircraft—the rudder mechanism and the back fifth of the plane—disappearing into the building,” he explained. “As soon as it slammed in, there was total silence.”

Two seconds later, five stories of windows lit up in bright orange “like a pinball machine.” Harris heard a whoosh like a barbecue grill igniting and saw a fireball blast through the north face of the building. A “big, black billowing cloud with orange flashes in it” burst into the clear blue sky.

The captain sat stunned for a moment before reaching for his marine VHF radio, the standard radio equipment installed aboard vessels large and small that operates over the “very high frequency” maritime mobile band. With one hand on the wheel, he pulled the microphone off its clip and depressed the button with his thumb. “United States Coast Guard, Group New York. Sailing vessel Ventura on one-six.”

“U.S. Coast Guard Activities New York to the Ventura.”

Here, Harris froze. The maintenance man had repeated the word three times in the instant after impact, confirming what Harris had witnessed. But now the captain couldn’t bring himself to say the word jet. “There’s been a tremendous explosion at the World Trade Center,” he said. “It looks like five to eight stories are on fire. You’re going to need some backup here.”

All protocol fell away. “What?!?” said the youthful voice on the other end of the transmission. In that instant, Harris felt the shift as the formality of a vessel captain calling the Coast Guard vaporized.

“It looks like a plane hit,” he continued, haltingly, explaining that he planned to head on foot toward the towers with his handheld and would radio back with whatever information he could gather.

Harris, calling just seconds after American Airlines Flight 11 had rammed into the North Tower, was the first to notify the U.S. Coast Guard of the unfolding disaster.

Word traveled quickly up the chain to the deputy commander of the Coast Guard’s Activities New York, who, as it happens, was also named Patrick Harris. That morning Rear Admiral Richard E. Bennis was out of town, leaving Deputy Commander Harris as the acting captain of the Port of New York and New Jersey, the Coast Guard’s largest operational field command. At the Coast Guard station in Fort Wadsworth on Staten Island, a watch stander interrupted the morning meeting with: “Hey, Captain, I think you oughta take a look at this.”

Harris stepped a few feet away into the Vessel Traffic Service (VTS) center, a dark room full of monitors, phones, VHF radios, and radar screens glowing brightly as they offered a detailed overview of more than 40 nautical square miles. Twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, operators manned this maritime equivalent of an air traffic control center, monitoring the movements of vessels traveling through the Port of New York and New Jersey. To prevent vessel collisions and groundings, expedite ship movements, increase transportation system efficiency, and improve operating capabilities in all weather, they tracked traffic by remote radar and live television cameras mounted strategically throughout the harbor, and communicated with each vessel via phone or VHF. On a typical day the VTS supervised and assisted about 750 large vessels passing through the port.

Suddenly, this was no typical day. All eyes were trained on the live feed from a dozen of the 16 strategically placed cameras that showed 1 World Trade Center, the North Tower, burning. On the television in a nearby break room, CNN reported that a small plane had hit the tower. This news left the deputy commander, a career aviator with 34 Air Medals from his Vietnam service, uneasy. As a pilot, he couldn’t believe that a small plane could have done this kind of damage.

So far, in the minutes before 9 a.m., the incident was land-based, not technically of Coast Guard concern, but a 41-foot search and rescue utility boat was dispatched to the scene, just in case. Harris grabbed the phone and dialed Rear Admiral Bennis who, at the time, was in Northern Virginia cruising down I-95 South with his wife. Get to a television, Harris advised. “We don’t know what happened, but a plane just hit one of the towers of the World Trade Center.”

One hour earlier, Tammy Wiggs had walked across the five-acre, stone-paved plaza at the heart of the World Trade Center complex on her way to the New York Stock Exchange. The newly minted Georgetown University graduate had held her new job as a Merrill Lynch clerk for only a week and a day. Although she wasn’t expected at 11 Wall Street until after eight, her determination to make a name for herself straight out of the gate had prompted her to leave her Upper East Side apartment at 6:15 a.m. for the chance to show her face, walk around, shake hands, and chat up the traders at the desk in 4 World Financial Center. She planned to be one of those traders one day. While most clerks stopped in for a meet-and-greet one or two mornings per week, 22-year-old Wiggs, a self-described “naturally competitive person,” planned to outshine them all with daily visits. Everyone would remember her face.

At about quarter to eight she’d finished making her rounds and headed outside. Relishing the bright morning sun, she crossed the plaza at the foot of the two 110-story towers that had claimed title, at their 1973 ribbon-cutting ceremony, as the world’s tallest buildings. The twin towers had since become the nerve center of the bustling financial district, a must-see tourist attraction, and a central focus of the New York skyline.

Along her way, Wiggs passed planter boxes, stone benches, a stage set for summer performances, and the public plaza’s cynosure at the center of a spill-over fountain: a 25-foot-high bronze sphere sculpture, created by German artist Fritz Koenig, that symbolized world peace through world trade. This was a fitting centerpiece to the complex that architect Minoru Yamasaki had designed as “a living symbol of man’s dedication to world peace” and a “representation of man’s belief in humanity.”

Now 50,000 people worked in the vast, seven-building World Trade Center complex that housed some 1,200 companies and organizations. Featuring restaurants, a shopping mall, and a belowground transit hub, the site saw an average of 90,000 visitors daily. Just six weeks earlier, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey had leased the property, now more than 99 percent occupied, to a private developer, Larry Silverstein, who’d agreed to pay the equivalent of $3.2 billion over the next 99 years.

But none of that was on Wiggs’s mind as she made her way to Wall Street. Ten minutes later, with a heady mix of exhilaration and fear, she stepped into the New York Stock Exchange coatroom, swapped heels for Steve Madden loafers, and donned her black, mesh-backed floor jacket with the Merrill Lynch bull patch on the sleeve. Then she passed through the turnstile and strode to her station in a room dubbed “the garage.”

Up close, the stock exchange floor looked in real life just like it did on television: a cluster of round islands littered with computer keyboards and blinking screens. What struck Wiggs most about the space, which at this hour thrummed with pre-opening-bell anticipation, was its gymnasium vastness. People milled about issuing good mornings, coffee cups in hand. Wiggs felt like the new kid—female at that—walking into a guys’ locker room.

She was standing in her spot at one of Merrill Lynch’s booths, checking the “breaks” to make sure all of Monday’s trades had gone through correctly, when she heard a thump that sounded like a truck hitting a building. It was 8:46 a.m. A murmur rose across the floor as television screens lit up with announcements that a small plane had struck the North Tower. At first the chatter centered around how this new development might fit into the trading day. But then, at 9:03 a.m., a collective gasp erupted.

Across the Hudson River, about five miles to the north, Michael McPhillips was working aboard a converted car ferry docked in Weehawken, New Jersey, that now housed offices for the ferry company New York Waterway. A lifelong mariner, he’d run away to sea at 16 and traveled the world aboard ships before taking a position as Waterway’s port captain, charged with supervising vessel deployment, terminal oversight, management of captains and deckhands, vessel maintenance, and Coast Guard compliance. He was busy checking the day’s schedule, making sure the ferryboats were running smoothly and on time, when a deckhand called to tell him the World Trade Center was on fire.

He drove a half-mile to the work dock and corporate offices, dialing his superiors en route. After coordinating with company vice president Donald Liloia and rounding up two mechanics to work as deckhands, McPhillips commandeered the ferry Frank Sinatra, which had been out of service with one of its four engines down. Confident that he could adjust the throttles to compensate for the downed engine, McPhillips pulled the boat off the dock and shot straight for the World Financial Center. As he stood in the wheelhouse, it looked like the whole top of the North Tower was afire.

New York Waterway, which carried 32,000 passengers on an average weekday, had no plan for what to do if a plane struck a trade center tower. But the company did have a protocol for dealing with service interruptions of the PATH train—the Port Authority Trans-Hudson Corporation’s commuter rail connecting New Jersey to Manhattan through tunnels under the Hudson River. Since the railway terminated right beneath the World Trade Center complex, there was little doubt that a fire would provoke a PATH shutdown, leaving New Jersey commuters hunting for other ways to get home. And so Waterway went immediately into stopgap mode to offer alternative transportation.

“Deployment was a piece of cake,” McPhillips recalled years later. It was rush hour, so most of the boats were already crewed-up and operating. Instead of letting the boats wind down, as they usually did by late morning, the managers ordered crews to keep running.

The white-tent-covered barge that functioned as the World Financial Center’s ferry-loading platform was swarming with people when McPhillips dropped off Liloia. The vice president would manage passenger boarding by land; McPhillips would oversee operations by water. The boats would work overtime until train service was restored. This plane crash was a terrible accident.

Just a fire. Everything will settle down by evening rush hour. With this thought, McPhillips set about leading ferryboat captains in transporting boatloads of people off the island.

Minutes later, Waterway’s director of operations Peter Johansen also arrived at the ferry terminal. He’d been standing in the wheelhouse of a company catamaran ferry bound from Weehawken to Pier 11 on the East River when he’d caught sight of the jet getting “sucked into” the North Tower. As the boat continued around the southern tip of Manhattan, Johansen could see that the force of the plane’s impact had blown out the windows on the opposite side of the tower. Smoke now poured out of the south face of the building as well. “Honestly, I think most people felt that it was a navigation accident. The reason I say that is because we continued around to Pier 11, the Wall Street terminal, and there were about a hundred people on board. Every single one of them got off and went to work that morning. And as they’re walking off there are envelopes and letters floating down from the sky.” At about 8:55 on a Tuesday morning, no one on that boat could have foreseen the scale of the trouble to come.

Unlike those commuters, Johansen had dropped his day’s plans and rerouted. Instead of attending a meeting of the Port of New York and New Jersey’s Harbor Safety, Navigation, and Operations (Harbor Ops) Committee, he’d directed a ferry to drop him at the World Financial Center to help manage the increased ferry traffic that would doubtless result from the incident.

When Johansen arrived at the ferry terminal, he and Liloia split duties, with Johansen manning the top of the gangway, permitting only as many passengers as could fit on the next boat to go down onto the barge, and Liloia at the bottom, designating which boats would go where. “Everybody was standing there. Nobody panicked,” Johansen recalled. “In the beginning we were taking people to their regular stops. . . . Later on it was just, ‘Get ’em across the river.’ So it was either Hoboken or across to Jersey City.” By midnight New York Waterway would use more than 20 different ferryboats to transport more than 160,000 people.

Less than a mile away from the World Financial Center terminal, FDNY Battalion Chief Joseph Pfeifer had seen the first plane hit and seconds later he called in to FDNY’s Manhattan Dispatch with both a first and a second alarm. Racing south in his battalion car, he realized that the 19 trucks those alarms summoned would not be enough, and he called in a third. “We have a number of floors on fire,” he explained. “It looked like the plane was aiming towards the building.” Reports from other units echoed his sense that this collision was no accident. They provided the first glimpses of the mounting disaster, painting a doomish picture.

8:48:09

Engine 1-0: It appears an airplane crashed into the World Trade Center. . . .

Squad 1-8: . . . looked like it was intentional. Inform all units coming in from the back it could be a terror attack. . . .

Engine 1-0: Roll every available ambulance you’ve got to this position. . . .

Engine Fire 5: Please have ambulances respond to West Street. We have several injured people on West Street here. . . .

When he pulled up in front of the North Tower at 8:50 a.m., Chief Pfeifer was the highest-ranking fire commander on scene. Looking up the west side of the building, he saw light smoke but no fire. He swapped his white chief’s hat for his fire helmet and yanked on his protective bunker gear—overalls, coat, boots— before stepping into the lobby to confront the biggest conflagration of his career. Shattered glass from blown out windows crunched under his thick rubber boots, and the first of one thousand firefighters summoned began streaming into the tower to report to the largest rescue operation in New York City history.

Although they couldn’t see what the fire and impact zone looked like from the outside, the firefighters in the lobby of the North Tower knew they were in deep trouble. The size of the gash and the intensity of the smoke and flames were beyond the fire-extinguishing capability of the forces they had on hand.

Minutes after Chief Pfeifer reached the North Tower, the division chief of Lower Manhattan Peter Hayden arrived on scene and took over. As Hayden later explained: “We realized that, because of the impact of the plane, there was some structural damage to the building, and most likely that the fire suppression systems within the building were probably damaged and possibly inoperable.”

Here, simple physics reigned supreme. Each single trade center floor stretched 40,000 square feet—nearly an acre. Even with multiple hose lines, each capable of dousing 2,500 square feet, the FDNY could not battle a fire that had already engulfed at least five floors. Very early on the chiefs determined that this was strictly a rescue mission. “We were going to vacate the building, get everybody out, and then we were going to get out. . . . We had a very strong sense that we would lose firefighters . . . but we had estimates of 25,000 to 50,000 civilians, and we had to try to rescue them.”

This monumental decision meant that all the companies now crowding the lobby to muster at the scene would not attempt to fight what would become the deadliest fire in U.S. history. Thwarting their evacuation efforts, however, was the fact that almost none of the building’s 99 elevators still functioned. To reach the upper floors, firefighters, laden with between 561⁄2 and 941⁄2 pounds of gear, would have to take the stairs, as would evacuees coming down.

Eight years earlier, elevator failures had plagued rescue workers, as well. At 18 minutes after noon on February 26, 1993, a huge bomb had exploded beneath the World Trade Center, killing six people (one of them pregnant) and injuring more than 1,000. Terrorists had planted a 1,500-pound bomb on a timer in a rented Ryder truck and parked it on Level B-2 of the underground garage.

The subsequent blast had opened a hole seven stories deep, cutting off electrical power and communications in significant areas of the twin towers above. The public-address system and even the emergency lighting system had failed. People (including a teacher and a group of schoolchildren) had ended up trapped for hours in elevators while evacuees using cigarette lighters made their way down dark and smoky stairways. Evacuation of both towers had taken more than four hours. “Without elevators,” Donald Burns, a chief on the scene of the 1993 bombing, had written in an after-action commentary, “sending companies to upper floors in large high-rise buildings is measured in hours, not minutes.” Now, the impact of the plane left rescue workers struggling once again with major failures in building infrastructure.

Damage caused by the jetliner collision had left some elevator cars, filled with trapped riders, stalled between floors. Other cars had reached the lobby level but failed to open. Screaming passengers banged on the sealed doors just feet away from firefighters gathering in the lobby. But amidst the sirens, the shouting, and the clamor of competing radios, their screams went unheard.

Also mobilizing were officers from the City of New York Police Department (NYPD) and the Port Authority Police Department (PAPD), charged with protecting the Port Authority’s customers, commuters, and employees. Ten minutes after the first plane hit, at 8:56 a.m., NYPD Chief of Department Joseph Esposito had radioed central dispatch calling for a “Level 4” mobilization, the department’s highest state of alert, equivalent to a “war footing.” Level 4 marshaled nearly 1,000 officers to the scene— 22 lieutenants, 100 sergeants, and 800 police officers from all over the city. Already an elite team of about 40 rescue specialists from the NYPD’s Emergency Service Unit (ESU) had arrived and set up a command post at Church and Vesey Streets on the northeastern corner of the trade center complex, right across the street from a Borders bookstore where a children’s story hour was set to begin.

Within about 15 minutes, New York City and the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey launched the largest rescue operation in the city’s history, deploying first responders, beginning an evacuation, and making the critical decision to focus efforts in the North Tower on rescue and not firefighting.

Meanwhile, the U.S. military, having received information about the hijackings too late to change the course of events, played catch-up as the attacks unfolded. Although the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) Boston Center flight controllers had learned by 8:20 a.m. that Flight 11 had probably been hijacked, the U.S. military wasn’t informed until 17 minutes later when, at 8:37 a.m., an air traffic controller at the FAA’s Boston Center called the Northeast Air Defense Sector (NEADS), a division of the North American Aerospace Defense Command, a binational U.S. and Canadian command charged with defending North American airspace.

FAA: We have a problem here. We have a hijacked aircraft headed towards New York, and we need you guys to, we need someone to scramble some F-16s or something up there, help us out.

NEADS: Is this real-world or exercise? FAA: No, this is not an exercise, not a test.

At 8:46, NEADS ordered to battle stations two F-15 Eagle fighters from Otis Air National Guard Base in Falmouth, Massachusetts, 153 miles away from New York City. The hijackers aboard American Airlines Flight 11 had turned off the plane’s transponder, and NEADS personnel were still searching their radar scopes for the airliner at 8:50 when word reached them that a plane had struck the North Tower four minutes prior.

Before the plane hit, Flight 175’s pilots had reported a “suspicious transmission” during which a Flight 11 hijacker keyed the wrong microphone and widely broadcast his announcement to passengers to remain seated. Shortly thereafter, between 8:42 and 8:46 a.m., their own plane was seized. The military remained unaware of the second hijacking. Although fighter jets got airborne at 8:53 a.m., they had no known target and were sent to military-controlled airspace off the coast of Long Island.

On the ground in Lower Manhattan, the rescue operation was taking shape. While first responders raced into the complex, civilians raced out. By 8:46 on the morning of September 11, an estimated 16,400 to 18,800 people were present in the World Trade Center complex. And, of course, the surrounding area was filled with homes and businesses as well. Lower Manhattan, the area south of Chambers Street and the Brooklyn Bridge, was home to 22,700 residents. It was also the fourth largest business district in the nation, with a private sector working population of 270,200 in addition to public sector employees. With the inclusion of tourists, students, shoppers, and other visitors, the area’s daytime population swelled into the hundreds of thousands.

New York City is the most densely populated urban area in the United States. The island of Manhattan, 13 miles long and 2.3 miles across at its widest, holds just 7 percent of the city’s land area but nearly 20 percent of its total population of 8 million people. Not surprisingly, the country’s most populous city has one of the most complex transportation systems, featuring nearly 23,000 center-line miles of roads, streets, and highways; approximately 500 route-miles of commuter rail; and 225 route-miles of rail rapid transit. The city is served by three major airports, and by the largest maritime facilities for passengers and cargo on the East Coast.

Given the difficulties of traveling by car in such a congested area, millions of commuters, visitors, and residents alike rely on public transportation. On weekdays in 2001, New York City Transit subways and buses—the largest such systems in the country—served 6.4 million passengers. Meanwhile, weekday ridership on PATH trains and aboard public and private ferries totaled 258,000 and 91,600, respectively.

Overseeing the bulk of this extensive transit network were the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, the New York City Department of Transportation (DOT), and the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA), which ran New York City Transit. At the first sign of trouble at the World Trade Center, officials and operators of these various transportation agencies acted almost instantaneously to protect passengers, personnel, and equipment.

One minute after the North Tower was hit, an MTA subway operator, who had pulled his train into Cortlandt Station, alerted the MTA Subway Control Center to an explosion at the World Trade Center, initiating emergency procedures. Simultaneously, a quick-thinking PATH train dispatcher ordered the PATH trains that were en route at 8:46 a.m. to speed through the trade center station and head back out without opening their doors. Within minutes PATH officials shut down services, rerouting or canceling trains. These steps kept passengers from entering the danger zone, but they hindered people’s efforts to exit as well. The split-second decisions that many made that morning ended up deciding their fates.