Women with hard hats and tool belts toil as equals down at Ground Zero

AT THREE O’CLOCK in the morning on a rainy Friday, three days after the World Trade Center collapsed, Lois Isaksen put on her hard hat, strapped on her tool belt and hiked over the Brooklyn Bridge. She was worried about the impact of the rain. “I wanted to come down and give respite to the workers. I didn’t feel like there’d be much time left [for survivors],” said Isaksen, a carpenter for eight years and a member of Local 608.

She didn’t have any trouble getting onto the site of the smoky ruins and rubble, a fact she attributed to her “union card, hard hat, tool belt.”

Respirator in hand, Isaksen was “ready to get right up to the pit, climb in and start digging, but they were pulling people back, even ironworkers.”

Because of the rain, the steel beams were too slippery to stand on safely, and concerns that other nearby buildings could collapse put rescue efforts on hold. Instead Isaksen, 37, from Brooklyn, helped unload trucks and cleared a roadway to make room for heavy machinery. “I didn’t do anything heroic,” she said, “but I would have done anything possible… handing out water, holding out a port-a-pan… Who in New York City isn’t feeling helpless?”

Isaksen is one of the many women who have worked at Ground Zero since the first plane hit. From firefighters to engineers to construction workers, women in nontraditional occupations have been toiling to rescue individuals and restore office structures nearby. Because dozens of companies have been working under emergency conditions, there is no accurate count on how many women are working in the wreckage. Though women have worked side by side with men for long shifts under dangerous conditions, some say they have been given short shrift in the media that has celebrated as heroes firemen but not the women.

Still, amid the rubble and ruins, whether they’re pulling steel beams from the wreckage or repairing telephone cables, the women say they have been treated as equals in ways that they haven’t always experienced on other work sites, where they say harassment still occurs.

On most construction sites, Isaksen says she has grown accustomed to “feeling like I’m on a runway” with all eyes on her while she works. “But this whole experience [at Ground Zero] is desexualizing… Sometimes in a tragic moment we lose our prejudices and our assumptions.”

The enormity of the World Trade Center recovery efforts seems to have changed some rules about work, according to Michelle Larson, deputy director of the Women’s Bureau at the U.S. Department of Labor. “With a task [like this] at hand, people don’t have time to think about preconceived notions… When you have a skill that you can contribute, people aren’t thinking about whether it’s a ‘man’s job or a ‘woman’s job,’ they’re appreciating the contribution.”

Rosemarie George, an ironworker for 16 years, contributed by working on the bucket brigade and helping separate beams for three days in mid-September. Because there weren’t enough torches, the 45-year-old grandmother from Brooklyn didn’t do much cutting, but George said her training helped her to rip screws to get the steel apart for easier removal.

She was careful to wear her Local 580 T-shirt on the site so people would know she was an ironworker. “Nobody ever paid me any attention, or said, ‘be careful’ or ‘watch yourself so you don’t get hurt,'” she said. “They recognized me as an ironworker, capable of doing the job at hand.”

The life or death nature of the job meant there was little time for other considerations. “You just knew there were innocent people under there… You’d do anything in your power to make sure they got out alive,” George added. “If that meant taking out piece by piece, digging holes in caves, it didn’t matter, you’d do it … We were just individuals working together on one common cause.”

Though she has since been reassigned, she’s been “pushing the big guys” to let her go back to the World Trade Center site.

Other female workers and managers at Ground Zero also experienced the urgency and collaboration. Beginning on Sept. 11, Victoria Sorvillo, 27, a general foreperson for Consolidated Edison’s gas operations division, worked for two weeks at a makeshift command center, coordinating the digging, cutting and capping of gas mains. She was responsible for keeping her team safe and maintaining communication between workers spread across a five-block by five-block disaster area.

After five years at ConEd, Sorvillo is accustomed to construction areas and didn’t think about being female until she saw another woman construction worker. “I took notice of her. It was nice to see we’re here,” Sorvillo said. She also noticed getting second glances. “The firemen do a double take and I get looks of surprise,” she said. “But, I kind of take pride in it. I’m glad I’m one of the few.”

While some women at Ground Zero felt like they were the only one, or one of the few, the overall number of women in non-traditional jobs has climbed steadily over the past generation.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, 1.7 percent of all carpenters in the United States last year were women, more than triple their share in 1972, while the number of female electricians quadrupled, but still accounts for only 2.7 percent of all electricians. Women have made greater strides as engineers, going from 0.8 percent in 1972 to 9.9 percent in 2000, and women now account for 3 percent of all firefighters, six times their ranks in 1972.

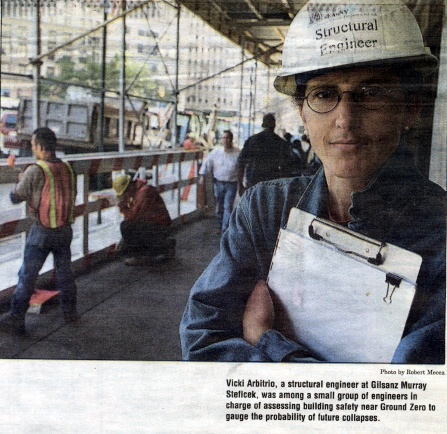

Structural engineer Vicki Arbitrio of Gilsanz Murray Steficek and a small group of engineers—including one other woman—were in charge of assessing building safety near Ground Zero to gauge the chance of future collapses. “We were a little obvious with our clipboards, traveling as a pack, standing in the streets and looking up at buildings,” she said.

The problems women face become barriers to employment access, which in turn keeps numbers low. “In construction… even in a boom economy women have trouble finding work,” said Jane Latour, director of the Women’s Project of the Association for Union Democracy.

There are many reasons for this, she noted. “One is that the contractor often hires people who look just like him. Because the numbers [of women in non-traditional occupations] are so low, women still have to deal with harassment and other power issues from men who still think these are men’s jobs.”

Louis J. Coletti, chairman and chief executive of the Building Trades Employers Association of New York City, disagreed that access to employment has been difficult. Open shop contractors may be able to hire anyone they want, but federal law makes it illegal for union contractors to skip over women on the list, he said.

“The construction industry has always been aggressive in recruiting women but we haven’t been successful, for whatever reason.”

Harassment is down dramatically, Coletti added, but still might be a factor when someone chooses a career. “That becomes an artificial barrier,” he said. In her 20-year career as a New York City firefighter, Brenda Berkman has confronted more than her share of barriers, including filing a 1982 federal sex discrimination lawsuit that resulted in the first hiring of women firefighters in New York City. “I probably saw a lot more women on the emergency site than I would see in my day to day,” said Berkman, a lieutenant at Ladder 12 in Chelsea.

Though the department began hiring women almost 20 years ago, New York City has just 29 female firefighters out of about 11,000 total. Women make up less than 0.5 percent of the department, while cities such as Los Angeles, Chicago and Houston have four to six times as many. “Women firefighters in New York are very conscious of being a very tiny percentage,” said Berkman, president of United Women Firefighters, a local group of FDNY women.

But digging in the rubble in full turnout gear made her somewhat anonymous. “All the women and men were working together, helping each other. But the minute you start to talk somebody will turn around to look,” she said. “They don’t expect to hear a woman’s voice.” And as a woman who has carried her message of non-traditional employment for women to the White House, Berkman sees women in the rubble as fighting “the Taliban misogynist attitudes toward women, namely that women are subhuman and cannot be trusted to be employed or to perform any civic duties. Americans and their allies are showing the world that women are strong, capable and patriotic … By recognizing the contributions of the women at these scenes, we are uniting our country in the efforts against terrorism.”

Yet some feel women’s contributions haven’t been recognized enough, especially given the frequent media coverage of the site.

Berkman has been acutely aware of language that excludes women, like the use of firemen instead of firefighter.

“I hope the public realizes that there are a lot of women who’ve been contributing and that they were from the very beginning, from when the first plane hit … We care as much and are trying as hard as anyone to find people.”

Kathy Rodgers, president of the NOW Legal Defense and Education Fund, has also noticed the lack of recognition of women’s roles. “They’ve been taking the same risks and facing the same dangers,” she said. “Yet what we hear about and what images we see in the media are ‘the men of the bucket brigade,’ the ‘firemen’ and the ‘policemen.’ … Even a tribute on Saturday Night Live for police officers and firefighters was all male. It’s not surprising that the women who have been working so hard and long are demoralized. They’ve been made invisible.”

However, women have received some recognition. At one of the many news conferences in the aftermath of the attacks, a reporter asked Mayor Rudolph Giuliani how the female firefighters were managing. His reply: Just like they are every other day, they’re fully up to the job.

While on site, most rescue and recovery workers spoke of trying to focus on the job at hand. Yet the burning rubble that was once the World Trade Center was a funeral pyre for thousands, and working there takes an emotional toll. The question is whether women were affected differently than men.

Sorvillo, the ConEd engineer, said being a woman has had no impact on how she’s handled the tragedy. “I don’t think I reacted differently from the guys. I don’t think I was more emotional. Everyone was in a state of shock. Everyone was calling home to their loved ones.”

But others saw real differences.

Rhonda Shearer, who with her daughter London Allen set up a supply depot in a Spring Street warehouse, said men, who are “more reticent in dealing with their feelings,” have looked to women for emotional support. “The emotional reality is that women are more attuned to emotions. Men know that. They turn to women for that,” said Shearer, 47, who usually works as a sculptor in Manhattan.

On her daily trips bringing rope, Sawzall blades, insoles and newspapers down to workers at Ground Zero, Shearer “got a window into World War II,” she said. “The men enjoy having women around as a break. They like to have a woman around to smile a loving, kind smile.” She cracked jokes with some of the rescuers, but others were “glazy-eyed, not wanting to talk at all,” she said. So she learned to tread lightly.

As cleanup efforts shift into high gear, some hope that women’s roles will continue and even grow. Several of the four construction management companies overseeing cleanup efforts have confidence that their female staffers will continue to be valuable in the months ahead.

Amec Construction has more than 300 workers on site, a number of whom are women, according to company spokesman Lee Benish, though he couldn’t say exactly how many. He said his company had no qualms about sending women down to the site to work as truck drivers, ironworkers, laborers, managers and project coordinators. “This is a gruesome task for everybody,” Benish said. “I personally don’t believe that anybody is insulated.”

Flushing-based Tully Construction has several female employees on-site, including surveyors, ironworkers and supervisors, according to director of safety, equal opportunity supervisor Bill Ryan. “We asked all our employees if they wanted to go. Some men have said they don’t want to go. None of the women have said they didn’t.”

As New York begins its multibillion-dollar rebuilding effort, new opportunities exist for women in every field to participate. “This could prove a wonderful opportunity to employ skilled women and to train new workers to do the critical work of rebuilding,” said NOW’s Rodgers.

The building industry concurs. Said Coletti: “We hope that through recruitment, more and more women will pursue construction as a career. We hope they will be involved in the rebuilding.”