Letter from America: An inside look at a White Power music festival

When she talks about her two young daughters, Amy’s whole tone changes. “They’re just so beautiful,” she says with a gentle Southern twang. “They got curly blond hair and blue eyes.” Suddenly I see. The glow on her face is not just maternal pride; it’s racial pride.

“This whole town is Klan,” Amy explains. This accounts for the trio of lawn gnomes with white hoods standing guard inside the entrance of the Last Chance Pawn Shop. For the third year in a row, the shop’s owner has offered up his backfield to Hammerfest, one of the biggest White Power music festivals in the nation. Standing in rural Georgia in a field ringed with trees turning red, orange and golden, I’m banking on my Irish-German features and blue-collar upbringing to get me through this adventure. No one knows I’m not in “the movement.” Just an undercover journalist curious about this hidden, hate-filled face of America.

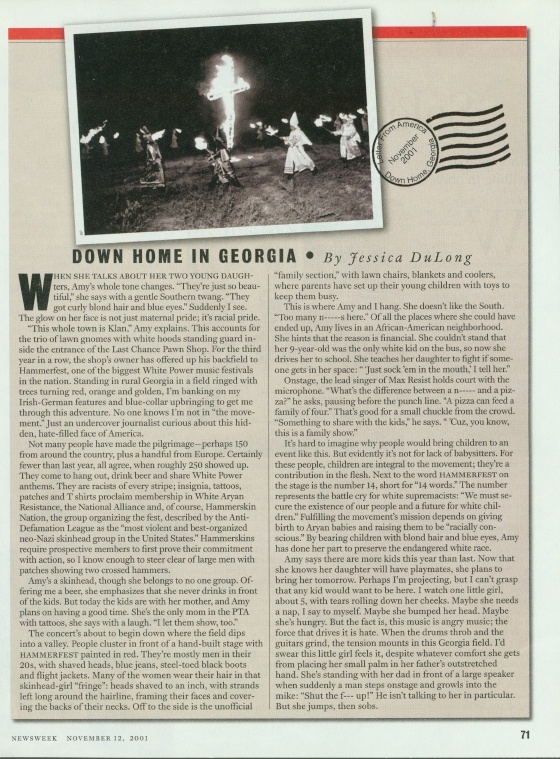

Not many people have made the pilgrimage — perhaps 150 from around the country, plus a handful from Europe. Certainly fewer than last year, all agree, when roughly 250 showed up. They come to hang out, drink beer and share White Power anthems. They are racists of every stripe; insignia, tattoos, patches and T-shirts proclaim membership in White Aryan Resistance, the National Alliance and, of course, Hammerskin Nation, the group organizing the fest, described by the Anti-Defamation League as the “most violent and best-organized neo-Nazi skinhead group in the United States.” Hammerskins require prospective members to first prove their commitment with action, so I know enough to steer clear of large men with patches showing two crossed hammers.

Amy’s a skinhead, though she belongs to no one group. Offering me a beer, she emphasizes that she never drinks in front of the kids. But today the kids are with her mother, and Amy plans on having a good time. She’s the only mom in the PTA with tattoos, she says with a laugh. “I let them show, too.”

The concert’s about to begin down where the field dips into a valley. People cluster in front of a hand-built stage with Hammerfest painted in red. They’re mostly men in their 20s, with shaved heads, blue jeans, steel-toed black boots and flight jackets. Many of the women wear their hair in that skinhead-girl “fringe”: heads shaved to an inch, with strands left long around the hairline, framing their faces and covering the backs of their necks. Off to the side is the unofficial “family section,” with lawn chairs, blankets and coolers, where parents have set up their young children with toys to keep them busy.

This is where Amy and I hang. She doesn’t like the South. “Too many n—–s here.” Of all the places where she could have ended up, Amy lives in an African-American neighborhood. She hints that the reason is financial. She couldn’t stand that her 9-year-old was the only white kid on the bus, so now she drives her to school. She teaches her daughter to fight if someone gets in her space: “‘Just sock ’em in the mouth,’ I tell her.”

Onstage, the lead singer of Max Resist holds court with the microphone. “What’s the difference between a n—– and a pizza?” he asks, pausing before the punch line. “A pizza can feed a family of four.” That’s good for a small chuckle from the crowd. “Something to share with the kids,” he says. “‘Cuz, you know, this is a family show.”

It’s hard to imagine why people would bring children to an event like this. But evidently it’s not for lack of babysitters. For these people, children are integral to the movement; they’re a contribution in the flesh. Next to the word hammerfest on the stage is the number 14, short for “14 words.” The number represents the battle cry for white supremacists: “We must secure the existence of our people and a future for white children.” Fulfilling the movement’s mission depends on giving birth to Aryan babies and raising them to be “racially conscious.” By bearing children with blond hair and blue eyes, Amy has done her part to preserve the endangered white race.

Amy says there are more kids this year than last. Now that she knows her daughter will have playmates, she plans to bring her tomorrow. Perhaps I’m projecting, but I can’t grasp that any kid would want to be here. I watch one little girl, about 5, with tears rolling down her cheeks. Maybe she needs a nap, I say to myself. Maybe she bumped her head. Maybe she’s hungry. But the fact is, this music is angry music; the force that drives it is hate. When the drums throb and the guitars grind, the tension mounts in this Georgia field. I’d swear this little girl feels it, despite whatever comfort she gets from placing her small palm in her father’s outstretched hand. She’s standing with her dad in front of a large speaker when suddenly a man steps onstage and growls into the mike: “Shut the f— up!” He isn’t talking to her in particular. But she jumps, then sobs.