On a recent Wednesday, just before 1 o’clock, about 30 sightseers gathered at the edge of Manhattan’s Battery Park waiting for Gray Line’s new trolley-bus to take them to Brooklyn. Among them was Stephanie Dougherty, 14, visiting from Dallas with her family. She’d been here once before when she was younger, but doesn’t remember much about the city.

Asked why she was bothering with Brooklyn, Dougherty just shrugged and pointed to her ticket. “It’s part of the all-loop tour,” she replied nonchalantly, just one of many accidental tourists now discovering Brooklyn by trolley-bus.

Mary Myers’ recent visit was far more deliberate. With the help of a volunteer guide from Big Apple Greeter, she brought her 79-year-old mother to Brooklyn from Morton, Ill., transporting her back in time to her childhood in Bedford-Stuyvesant through the days she fell in love with her husband.

“Mom hadn’t been back in 30 years,” explains Myers, who lives in Aurora, Colo. “She was smiling a lot.”

Ella Gross and her husband, George, of Annapolis, Md., were visiting their son, a recent transplant to Brooklyn, when they stumbled across a listing for Green-Wood Cemetery tours, offering looks into the lives and times of those buried in the country’s third rural cemetery, founded in 1838. They figured it would be a unique way to learn about the borough.

“It adds a lot of depth to the visit,” Gross explains. “Some people would think it’s sort of morose to visit a cemetery, but the people here had fascinating lives with all these connections to art and to history.”

Whether guided by curiosity, happenstance, art and music, or nostalgia, more and more visitors to New York City are stopping in Brooklyn. They’re venturing beyond the typical tourist trio — Empire State Building, Statue of Liberty and a Broadway show — to see the city’s most populous borough.

Since he took office in 2001, Borough President Marty Markowitz has sought to lure tourists. “You can travel the world and you don’t need a passport in Brooklyn,” says Markowitz, who considers himself its chief advocate and biggest booster. With help from Brooklyn’s Chamber of Commerce, NYC and Co., business owners and others, Markowitz’s efforts to establish Brooklyn as a tourist destination seem to be paying off for attractions and businesses nearby. While overall numbers for Brooklyn tourism are hard to come by, rising attendance figures and increased ticket sales at some of Brooklyn’s hottest attractions begin to paint the picture.

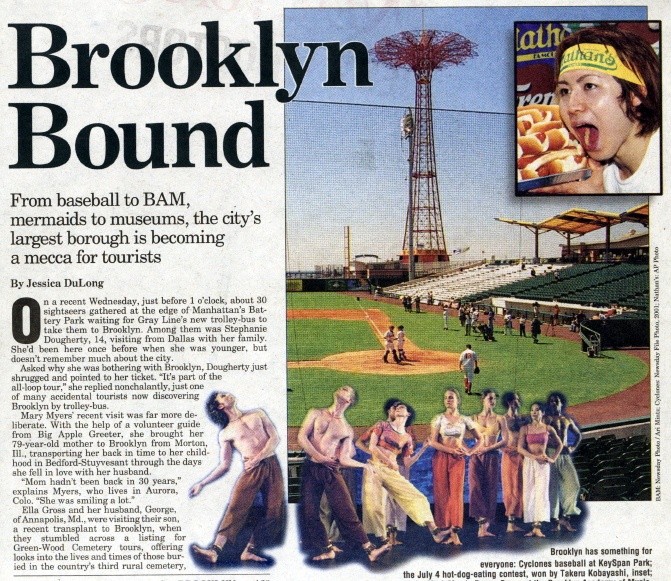

The first place to look for growth is Coney Island. During its heyday in the 1930s, forties and fifties, Coney Island routinely drew 40 million-plus visitors a year to the beach, amusement parks and world-famous Nathan’s hot dogs, said Kenneth Hochman, president of American Media Concepts, a Brooklyn-based ad agency that promotes the area.

After a drastic decline in the 1960s, seventies and eighties, the area began a restoration, starting with a beach rebuilding project in 1994. Coney Island’s visitor count dipped to about five million visitors in 1993, but by last summer had climbed to an estimated 10 million.

“The Cyclones are the key that unlocked the door to Coney Island,” says Hochman, referring to the Mets farm team that plays at 7,500-seat KeySpan Park. “They sold out every night for the entire first season in 2001, bringing a quarter of a million visitors.”

Carol Hill Albert, co-owner of Astroland Amusement Park, operator of the many rides on Coney Island, including the world-famous 76-year-old Cyclone Roller Coaster, agrees the Cyclones have helped.

“There has been a measurable increase in business after the games,” she says, declining to discuss revenue or ridership. “Not only are there more people, but … they’re more suburban.”

Roberto Mora, owner of the Coconut Juice Bar, has also noticed the new customers. “It’s good that middle class people come to Coney Island,” he said. “They spend money.”

Though revenues were up 15 percent to 20 percent last year, Coney Island’s small business owners say long spring rains and the closing of the Stillwell Avenue MTA station have made this year the slowest in a decade.

There have been days, Mora explains, where he makes only $50 instead of the $500 he would make on a good weekday last year. “What happens if we don’t have good transportation is they kill us,” he says. Ultimately, the May 2004 completion of the new MTA station, featuring a museum and retail spaces, should aid Coney Island redevelopment.

Meanwhile, many of the borough’s cultural institutions report spiking ticket sales and increased attendance. The Brooklyn Academy of Music, for example, had a record year in fiscal 2003, with ticket sales of 400,000 and $9 million in revenue. BAM, a performing arts complex in Fort Greene that includes an art-house cinema, a jazz cafe, a book and music shop, and two full-size theaters, presents everything from Shakespeare to flamenco to Taiwanese dance. Most of BAM’s audiences hail from Manhattan, though the percentage of Brooklyn-based ticket buyers has risen from 29 percent in 1998 to 48 percent in fiscal 2003, said spokeswoman Sandy Sawatka.

Though it’s true that many Cyclones fans and arts audiences are in fact locals, the rich assortment of activities is helping to create what Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce president Kenneth Adams terms the “critical mass” of attractions crucial to drawing out-of-towners. That array of events and institutions draws “a tremendous range of visitors by income, age and ethnicity,” he says. “The result is a bigger buzz and a greater appeal across the board. … You’re drawn in for a specific activity and you realize there’s so much more.”

For example, people heading to BAM to see U Theatre, one of Taiwan’s most celebrated dance troupes, perform “The Sound of Ocean” in October could dine beforehand at Saul, described in the new Brooklyn Zagat Guide as “heaven on Smith Street.” Then, they might come to discover that Boerum Hill is rife with trendy shops worthy of a return visit.

To maximize those discoveries, the borough president’s office is using a cultural tourism development grant from NYC and Co. to fund posters and advertising, as well as four portable kiosks shaped like ice cream carts. Beginning July 12, these carts, stocked with information about Brooklyn sites and events, debuted at the Brooklyn Bridge, Grand Army Plaza and Coney Island. This fall, the office also plans to open a tourism center in Borough Hall.

Brooklyn has come a long way since the days when teenagers flooded the Brooklyn Paramount theater for doo-wop concerts, then tipped back egg creams at Junior’s Restaurant. Traces of Old World Brooklyn still exist: Russian immigrants stroll the Brighton Beach boardwalk, Hasidic Jews push baby carriages in Williamsburg, and Greenpoint residents nibble Polish pastries. Yet through the seventies and eighties, high crime rates and economic decline gave Brooklyn a reputation for danger.

“If you talked to anybody they’d tell you Brooklyn had a gangy, hoody, mobster background,” says Joy Glidden, founder of the d.u.m.b.o. arts center and a Brooklyn resident since 1989.

Many in Brooklyn’s tourism industry predict that rediscovery of the borough will be the inevitable, natural by-product of Brooklyn’s resurgence. “Brooklyn is continuing to come back in terms of having a place in the public consciousness … with its restaurant rows on Smith Street and with Williamsburg, known for its nightlife and creativity,” says Norman Oder, founder of Brooklyn-based New York Like a Native tours. “As I say at the beginning of all my tours, Brooklyn has the strongest single identity of any of the outer boroughs. It, alone, was a separate city in the 19th century.”

He says he’s seen a steady increase in interest in tours of Brooklyn. Though most customers are locals, Oder has given tours to European tourists, particularly Germans interested in seeing Williamsburg, and learning about its Hasidic Jewish community. Though he declined to give numbers, Oder says his revenue has more than doubled since he started as a guide in the spring of 2000. He says he’s noticed “people who are adventuresome like coming to Brooklyn.”

John Cashman, a sort of Irish-Catholic Morty Seinfeld in sky-blue polyester pants, running shoes and a blue Ebbets Field cap, leads tours at Green-Wood Cemetery. While waiting for stragglers recently, he cracked jokes, setting the tone for the two-hour tour. “I’ve been in Green-Wood Cemetery over 50 years,” he says, noting that he used to cut the grass here as a teenager.

Since 1989, the former police sergeant, a native of Flatbush, has been giving cemetery tours, pointing out the grave sites of people such as Dr. William Stewart Halster, the surgeon who initiated the use of rubber gloves in hospitals; Walter Hunt, inventor of the safety pin; and Charles Barnes of Barnes and Noble. He gives five tours and wears a different hat for each. By now, he says, he’s taken thousands of people on walks along the cemetery’s 478 acres.

Most visitors to the outer boroughs have been to New York City before, says Liz Smith, an official with Big Apple Greeter, a nonprofit group of New Yorkers who volunteer to show off their neighborhoods. Architecture was the number-one reason her visitors last year cited for wanting to see Brooklyn, she says. History and music were next.

And as was the case with Myers and her mother, who used Big Apple Greeter’s services, family history is another big motivator. “They say one in seven people has a connection to Brooklyn,” says Smith. “If you have a grandmother who used to talk about sitting on the stoops of Brooklyn, it can be kind of fun to go see it.”

Those who want to see major attractions and not the old neighborhoods can catch one of Brooklyn’s newest tourist promotions — Gray Line’s new trolley-bus. In May, the company added a Brooklyn Loop to its signature hop-on, hop-off tours. With stops at Old Fulton Landing, the Brooklyn Museum of Art, the Brooklyn Botanic Garden and Junior’s Restaurant, among others, the Brooklyn Loop tours are bound to increase foot traffic and bring in many tourists who might not otherwise leave Manhattan.

Gray Line tour guide Fabrice Lecler explains visitor interest this way: “After getting lost in the mass of skyscrapers in Manhattan, visitors like the small-town feel of Brooklyn. They like the fact that people talk to each other here … that they say hello to the local corner guy.”