An excerpt from the original essay published in the collection, “Steady as She Goes: Women’s Adventures at Sea” (Seal Press, 2003).

I’m beginning to sweat diesel. Profuse heat shakes off the five 600-horsepower diesel engines that power the John J. Harvey, a retired New York City fireboat. I savor the breeze that greets the back of my neck on its way down the stairway from the main deck.

As assistant engineer, my place is down here in the engine room. Above decks passengers sip beers and take in the Manhattan skyline, and meanwhile I steal glimpses of the harbor through round portholes in the hull just above the water.

At the control pedestal, my eyes dart across the 30 gauges that indicate health or trouble in the engines while I wait for the clang of the next signal from the captain.

On a bell boat like this one, the captain stands in the wheelhouse. He sends signals down to the engine room with a ring and a twitch of the red arrow on one of two telegraphs, which are brass dials that hang like clocks on either side of my ears, one on the port side, one on the starboard. It’s my job to control the spin of the propellers that steer the boat and regulate its speed.

On my first day at the controls, I had an audience of men. One of them even had a video camera. Never before had a woman run these engines. The pedestal was designed for someone six feet tall, and I’m five-five, so when the captain signaled Full Ahead, I had to stand on my toes to swing the telegraph pointer all the way into position.

Sweat pooled, sticky where the plastic earmuffs sat on my cheeks, beading up and running over my temples, and trickling off my jaw. I didn’t dare take my hand off the prop levers to wipe away the drips. Between signals I stood at attention, my body rigid, my mind full of numbers. Props at 100 rpm for slow, 200 for half, 300-plus for full. Don’t let the amps climb past 1350. Run each engine at 11 hundred.

At the end of the trip, the captain shook my hand. “Very responsive,” he said.

…

Words have a way of hanging suspended, lifeless, until you find a way to attach meaning to them. These days I find words from my childhood flooding back: camshaft, crankshaft, bearings, bushings.

I remember Shop Days as a slinging of names I couldn’t keep track of – words for vehicles, customers, parts stores, tools. My dad is a foreign-car mechanic and growing up, I often spent the day with him. There’s a running joke in my family about how when my older sister, younger brother and I went to the shop my dad had the girls, ages ten and seven, sorting nuts and bolts while the three-year-old boy worked with him fixing cars.

Sometimes my dad took us kids with him to the machinist’s shop to drop off brake drums for resurfacing or to get engine blocks rebored. The machinist, gaunt and grey-skinned, always kept quiet. The walls of his greasy shop were lined with small cardboard boxes, their facing edges angle-cut like candy bins full of screws, springs and shims. I’ve since learned to name the tools that rested on workbenches above my head: drill press, milling machine, lathe.

The machine shop smells of grease, metal, and old man mixed with fumes from the donut shop next door. These visits were marathons of patience. I’d watch the machinist pivot in his swivel chair. I’d peer over the edge of a smeared bench, littered with small parts. Despite the urge to roll the metal bits between my fingertips, I kept my hands in my pockets. The “don’t touch” rule was implied, though never spoken.

…

In the six months since my first day at the pedestal I’ve become the fastest operator on the Harvey’s crew. When the boat is called to navigate tight quarters, the captain, a retired firefighter who’s piloted this boat for more than 20 years, wants me at the controls. While Harvey passengers take in the salt air I hide in the bowels of the boat like Oz behind the curtain.

The buzz of the vibrating engines travels through the soles of my steel-toed boots and up my feet, which swell with the heat. I stand on an up-turned wooden crate that gives me the height I need. There’s a particular drone of the engines at 11 hundred rpms. An occasional higher-pitched whine tells me that engine five, the one with the worn-out governor, has dipped to 10 hundred. I nudge the throttle and settle back into the hum of balance. Any bounce tells me to even out power to the two screws so they stop fighting each other.

I take the swoop and tilt of the current at the hips. And though I can’t hear the slosh of bilge water over the din of rumbling engines, I can see it move under the floor. The river seeps in through a porthole on the starboard side, trickling a burnt orange trail of rust across the thick white paint inside the riveted hull.

Like every vessel, the Harvey fights a constant silent battle with the salt water that buoys her.

Standing at the pedestal is meditative, but my head quickly fills the space. I picture my dad climbing down the narrow metal staircase from the deck. And though he’s never been on a fireboat, he’d recognize the components of each engine, from the fuel lines to the flywheel. He’d understand the concept of throttling down before engaging the air flex clutch. He’s a mechanic. I’m not.

…

One hot summer day when I was twelve, I convinced my dad to let me go to work with him. In our family cars meant power. I was older by then, so he’d have to let me do more than sort nuts and bolts.

One of the day’s jobs involved repair work on the front end of my mother’s Volvo station wagon. When the work was done, Dad handed me the air gun, told me to bolt the tire back on, and walked away.

I still recall the rush when I hefted the thing in my palm. I fingered the trigger with the sense of importance and risk that power tools bestow. I felt the torque in my wrist and heard the screech of the gun turn into a sputter as the nut tightened, then stiffened on the bolt. I methodically tightened each lug nut according to patterns I knew: I started at the top and worked my way clockwise around the wheel. I remember my sense of accomplishment when I was done.

The next day my father screamed at me – eyes red, spit flying.

“You could have killed your mother,” he yelled. She had been cruising at 75 mph in the far left lane on the highway when she felt the first wobble. She managed to pull over but the wheel could have spun right off the axle.

My face went hot. Only then, did he tell me I should have tightened alternating nuts, in a star pattern, staggering turns so the wheel would sit evenly.

…

I land each command as the signal comes down, pushing the prop levers quickly and smoothly. The ten months since my first boat trip show in the muscles in my arms and in the callouses on my palms and fingers. I take pride in my ability to discern who’s at the helm with just a few short clangs. I’m fine-tuning my docking skills – anticipating orders by watching the approach of the pier through the portholes. The beauty of old technology is how physical it is.

As assistant engineer, I could get away with playing trained monkey, never leaving my spot at the pedestal. But I’m hungry to understand every aspect of this 130-foot, 268-ton, steel-hulled vessel that is among the most powerful fireboats ever built. There is so much more I need to know about the power plant’s complex systems. I’m waist-deep in an electro-magnetism textbook, trying to wrap my head around diesel-electric propulsion, one concept at a time.

I read and collect my questions at the pedestal while we’re underway. Then, at the end of each trip, after twisting shut the valves that provide raw water to each engine, I stand in the baking, semi-dark engine room, holding a flashlight and talking shop with Tim, the chief engineer. My dad would like Tim.

On my first day at the stand, Tim corrected me when I faltered, wordlessly wrapping his long fingers around my small hand on the portside lever and pulling it back to Slow Astern as the captain had commanded.

Now he patiently explains the mysteries of motors and magnetism. He leans over to draw chalk diagrams on the floor. He opens the camshaft housing to let me see the angle of the air inlet ports on a cylinder. He walks through the routine conversion from ship’s power to shore power – again, because I still don’t get it.

…

When I finally bring my dad to the boat he nearly bursts with pride. I feel a tinge of nervousness as walk him through the paces. I describe how the engines produce the electricity that powers the two propulsion motors.

I show him the redundancy of the system – how we can operate with fewer than five engines by swapping over to auxiliary generators. I explain that the only things running direct-drive off the diesels are the water pumps.

He punctuates each of my explanations with one of his signature phrases: Wow. That’s ace. That’s dynamite. Though he’s a gasoline-engine mechanic who doesn’t think much of diesel, he knows which questions to ask.

Later, after I pry him out of the engine room and the family heads to dinner, my father asks me about the fuel system. He’s been puzzling over the open drip-cups that collect unburned fuel oil.

“The runoff ends up in the sump tank below the deck plates,” I explain.

“Nah. Nah. Nah. It can’t be like that,” he insists. “There’s no opening in the system.”

“It’s not a closed loop,” I maintain, while the rest of the family looks on. “The sump tank catches the excess and we have to pump it back into the main tanks.”

I remember a night years before when my dad attempted to explain internal combustion to his kids at the dinner table, twisting forks into crankshafts to demonstrate how the parts moved together. I remember how desperately I wanted his makeshift visual aids to etch a comprehensible, working model into my head – to carve out understanding that would stay.

“I dunno,” I say, even though I’ve emptied the sump tanks myself – fuel oil sloshing from the bucket onto my pant leg. “I dunno. Maybe I misunderstood.”

The next day I check with Tim.

“You’re right,” says Tim. “It’s an open loop.”

…

I’m standing in my usual spot at the control pedestal, dwelling on the fact that yesterday I’d flubbed up resealing a cylinder adapter in the number-one engine. So today we had to pull off the dock, running on four engines until Tim could fix my mistake.

As my eyes bounce over the dials – scavenging air above three, lube oil pressure above twenty psi, starting air steady at 200 pounds – I try untangle the familiar knot of my own incompetence.

Suddenly, there’s a pop, and a flash under the deck plates on the port side.

You can’t really hear a pop over the whine of five eight-cylinder diesels. But an impact with enough force transfers sound at its most elemental level: you feel it hit.

On a boat like this, any quick change in light can make you nervous – I’ve often spun my head around on alert when a person on deck walks past the engine room door and momentarily blocks the sunlight from pouring down the stairs. Here, in the rush of noise and vibration, noticing any slight fluctuation is key. Tim and I joke about hyper-vigilance. But here below decks, surrounded by the pounding conversion of heat into work, combustion into power, hyper-vigilance isn’t paranoia – it’s prevention.

My mind races with the flash. No way that was caused by sunlight.

The yellow-orange glow reflects off thick water mains below the floor. The spark lights up parts of the bilge I’ve never seen before. The small tornado of white smoke that follows the pop, sets my heart to ricochet.

I can’t find Tim. He must have slipped off to work on something in the back. I’ve never used the panic button before, but I reach for it now. It’s not red, but black with the word “PANIC” spelled out below it, scrawled in sloppy magic marker.

We’d laughed when Tim connected it to a loud siren that can be heard throughout the boat. You have to hold the button down for three seconds before it makes a sound, but right now, half a second feels too long, and I lift my finger off before it gets the chance.

I crane my neck around the number-two engine and there I see Tim walking toward me. My wide eyes communicate my alarm, but my outstretched finger gives direction. We peer over the edge of a deck plate into the gap beside the number-five pump. I see fire.

Urgency sears through Tim’s body, his muscles ready to move. He stretches an arm and yanks the port prop control lever into neutral. I hop in front of the pedestal and pull the starboard lever to a stop. Then at Tim’s single-gestured instruction I slam all the throttles to idle and signal the wheelhouse: Full Stop.

Tim reaches for a long screwdriver to pull up the deck plate. He digs the flat metal tip into the corner of the plate to catch the underside. I tug the fire extinguisher off its bent metal bracket and set it within reach. We pry up the plate. Flames shoot up from below. I don’t think about the slick of fuel oil and lube oil sloshing in the bilge.

I hand Tim the extinguisher. He yanks the pin, pulls the trigger, and with a few short sweeps the foam suffocates the blaze. For a moment everything stops. The engine room seems suddenly suspended. There is no noise.

The Full Stop has aroused concern in the wheelhouse so Don, one of the retired firefighters who volunteer on the boat – the one who had the video camera on that first day – appears in the engine room. He nearly falls into the bilge because we’ve removed the deck plate.

Tim waves “Get out!”

So Don swings over to my side. I push him back, both my palms pressed flat against his chest. “The captain wants to know what’s going on,” he shouts, peeling the plastic earmuff from my sweaty cheek so I can hear. The Harvey’s in the middle of the busy Hudson, in danger of colliding with countless other vessels. The captain has nothing but manual control of the rudder. He can’t steer without power.

“Tell him we had a fire, but it’s out,” I shout back, and Don makes his way forward again.

Tim heads aft to the rear of the engine room and shorts out the electricity to the whole port side. He shuts down the number-five engine then signals to me to throttle the others back up. Starboard-side power is better than none at all.

Tim bends to reach the scorched contactor cover, swiping at the foam with a rag. I hustle to the other side to help him lift and slide it up and out of the way. Effortlessly, we navigate together in this space. For nearly a year I’ve been hawk-eyed, watching him work. Now, I can almost predict each step.

Down on his belly, Tim reaches below the contactor with his rag. Without seeing it, I smell the source of our fire: a jet of fuel oil shooting from the pipe that supplies the engines. Don returns again.

“I need a hose clamp and a piece of rubber,” Tim shouts at me.

Maybe I actually hear him say this. It’s equally possible I am reading his lips. He and I both look at Don and point. Don should take the pedestal. He shrugs. He doesn’t know how.

I run to the tool room. Nothing. Then I remember a box I moved to the bench behind the number one. I rush back and dig out two clamps and a stretch of hose.

With cupped fingers, Tim indicates he needs a patch. I yank the Swiss Tool off my belt and split the hose down the middle. “This big?” I ask silently, forming a circle over the rubber with my thumb and index finger. The patch fits.

A hose clamp fastened around the leak staves off further disaster, but we call off the afternoon’s voyage and limp back to the dock on two engines. The captain has minimal maneuverability, so I concentrate on my part: zero-second response time.

Between calls I feel the smooth brass control levers heat up in my grip. We land at the pier with hardly a bump.

…

Twenty-four degrees is just too damned cold for automotive repair. Every frigid wrench I pick up cramps the bones in my hand. My dad works freelance now, out of a barn he rents on what used to be farmland. Winter snuck up on him, he says, and he has yet to buy heating oil.

This small job, replacing a torn CV boot on my car, is harder than it ought to be. Cold metal doesn’t cooperate: it doesn’t want to pull apart, or come together.

My car is suspended on the same lift Dad’s had for years. It was a big investment when he bought it. I remember the shiny blue look of it new in his old shop. Now I’m standing here holding the lever. The lift can move in only two directions – up, or down. You’d think I’d be able to master it, but I have to come up with a rhyme to remind me whether to push or pull.

Once the front wheel is at eye level, I hand my dad the air gun with the right socket already attached. The first whirring blast of the thing sends me back years. The air compressor kicks on. I wish it would throw off some heat.

With the wheel removed, we gain quick access to the drive axle. The exposed end is suddenly familiar. I realize this could be the same repair done on my mom’s car seventeen years ago. I pivot the droplight so the back-shield faces my dad to keep from blinding him.

When he falters with the cotter pin I hand him my Swiss Tool, pliers open and ready. When the joint won’t separate, I scour the cluttered benches in search of something heavy to hammer with. I use what I’ve learned to help me navigate. I try not to wonder if he notices a difference.

…

I’m shivering in the uncommon silence of the engine room. It’s been two months since our last boat trip of the season. Few people get to see the old boat this way: quiet and gently lilting in her berth.

A faint drip comes from some pipe low beneath the deck plates. The familiar huff of diesel scrapes at the back of my throat. By now I can tease apart the smell the way some people discern hints of oak, cherry or chocolate in a fine wine – an exhaust-fume bouquet wedded with a richer base note of lube oil and a hint of bilge water.

A thin light glints off the shiny brass of the starboard-side telegraph and flits across the gauges. Though it flickers like a campfire, the light is actually reflecting off the river water that laps at the portholes. Tim and I have drained down the engines to keep them from freezing.

There’s something slightly sad and embarrassingly intimate about seeing the boat so still. In my head I tally off the list of repairs we hope to accomplish: patching the mufflers, rebuilding the compressor motor, and polishing the pump shafts. All this before spring.

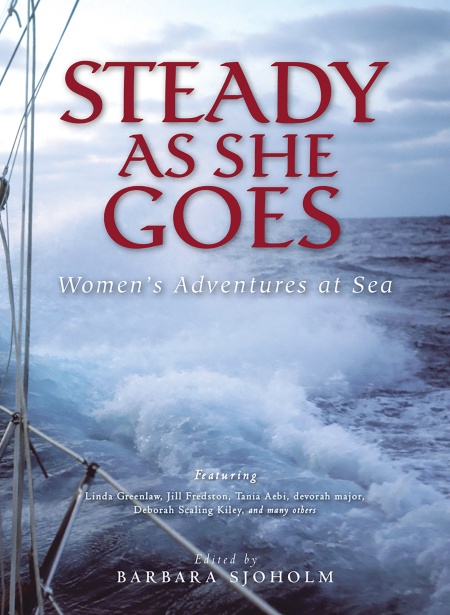

About Steady as She Goes: Women’s Adventures at Sea

Edited by Barbara Sjoholm | Published by Seal Press

Veteran seafarers and anyone who has dreamed of running away to sea in their very own boat or simply savored the smell of the salty air on the water’s edge will be inspired by this well-crafted and varied collection. Steady as She Goes is both a testament to women’s enduring relationship with the sea and a gripping and illuminating read. Twenty essays by Jessica DuLong, Linda Greenlaw, Jill Fredston, Bernadette Bernon, Tania Aebi, Devorah Major, Kaci Cronkhite, Holly Hughes, Andromeda Romano-Lax, Jennifer Hahn, and many others.

Whether commercial fishing in Alaska’s unforgiving waters, racing tall ships off the coast of Australia, kayaking in the enchanting Sea of Cortez, or learning the antiquated mechanics of a New York City fireboat, these women work and play at sea, spinning harrowing adventure yarns and relaying quiet moments of revelation surrounded by the vastness of the ocean. This unique and long-overdue collection shatters once and for all the myth that the sea is solely the domain of men.

This collection of salty yarns by and about women who sail calls itself the first of its kind…Other highpoints include Jessica DuLong’s stylish “Below Decks,” tracing her lifelong enthrallment with mechanical doodads, from her father’s auto shop to the diesel-powered John J. Harvey, a retired fireboat on which she’s a crew member plying the Hudson River, and Jennifer Karuza Schile’s story of her fishing family, “Happy Jack and the Vis Queens.”…